Sharon Thomas, Regina Res Publica, 2004. A response by Dr Gráinne Rice

Sharon Thomas showed me an image of Regina Res Publica (Gina) one of the very first times we met in the early 2000s. She was back in Glasgow for a visit from New York where she was living at the time. I was instantly fascinated by this painting, so I am delighted that she has asked me to write a response to it almost 20 years later. Always an artist in dialogue with art history, it was in Thomas’ words ‘painted in anger’ as an act of retreat and resistance during her time living and studying in the US (2001-2005). Her time there coincided exactly with the period rhetorically known as the War on Terror that began with the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and continued into invasion of Iraq in 2003. By reexhibiting Gina on the twentieth anniversary of this internationally destabilising period, Thomas is intentionally challenging us to reflect on global, and personal, political change in the intervening years. This was made even more urgent since Kabul and other Afghan cities were re-captured by the very same Taliban fighters those wars were meant to eliminate, with the knowledge these seizures herald terror and repression into women’s lives.

Gina originated in New York in the aftermath of what is officially called the September 11 Attacks on the World Trade Centre, and colloquially termed 9/11. The view from the window of the small Downtown studio where Thomas made Gina (and her sister canvas New Jerusalem) was the brick wall of the adjoining building. She worked to a soundtrack of demolition during the Lower Manhattan clean-up operation with the chemical fumes of aviation fuel permeating everything. Thomas came to New York as a Vilore scholar to undertake her graduate studies at the prestigious New York Academy of Art (the Academy). The terrorist attack occurred within a couple of weeks of taking up her place, and in the years that she lived there, New York was a city still processing its collective trauma after the attack. Thomas said she felt ‘trapped’ in the city. The act of painting, and rural spaces she created, were acts of escapism: ‘when I’m painting, I’m free’.

The girl on the bike in the foreground of the painting is based on a found image of bassist Marcie Bolan from underground 90s Detroit Indie band, Slumber Party. In the painting Thomas uses the redhead as her stand-in, her alter ego in the vision of rural escape. Gina stands atop a rocky outcrop, astride a retro-looking Schwinn bicycle projecting into the landscape; she directly engages the viewer with a glance over her shoulder. She seems to embody Thomas’ fierce motto, ‘I will take anyone on’.

For 2021 audiences there are many contemporary resonances in Thomas’ rural vision. In the 18 months or so since the COVID-19 pandemic began, we have come to better understand how nature can be a soothing or healing space, a place of solace in difficult times. In painting her escape from the post-9/11 destruction, Thomas returned to the landscape of her childhood, an embellished vision of the Cheshire Plains with a super-exaggerated rendering of the rocky crag on which Beeston Castle sits. From her bird’s-eye view Gina is queen of all she surveys. Thomas’ dreamy landscape is at once romantic and agricultural, the patchwork of fields recalling the country seen from an airplane, or the aerial views of her former Glasgow School of Art tutor, Carol Rhodes. The imagery of the girl on the bicycle is a powerful symbol of freedom for Thomas. From early in its history, the bicycle offered women opportunities to travel independently in relative safety. This is notable in the visual culture of the suffragette movement, where the bicycle motif appears in both anti-Votes for Women satire, and as an expression of the ideal Modern Woman.

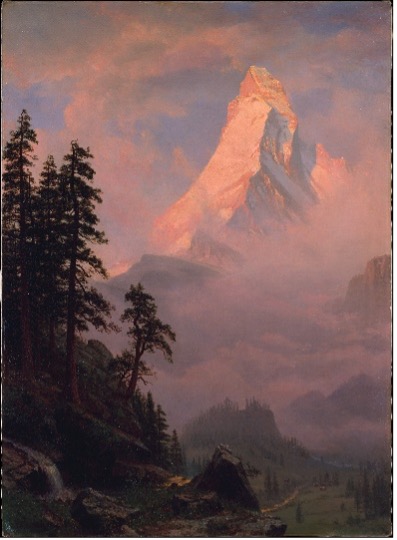

Gina is a large painting (167.6 x 224.8 cm) painted in the manner of the Old Master landscape, which, as the name suggests is an almost exclusively male genre. Thomas’s technical prowess was honed by the avowedly academic studio teaching she experienced at the Academy. The work evokes iconic paintings by Rubens, Gainsborough and the Hudson River School painters that she encountered during her frequent visits to The Metropolitan Museum. Albert Bierstadt’s Sunrise on the Matterhorn, is a specific reference point for Gina’s composition.

Figure 1: Sharon Thomas: Regina Res Publica, 2004

Figure 2: Albert Bierstadt, Sunrise on the Matterhorn, after 1875 Gift of Mrs. Karl W. Koeniger, 1966 The Met, OA Public domain

Never an artist to shy away from a challenge, Thomas set out to take on the genre of History painting, to establish herself within the same stylistic territory as her artistic forefathers. The Latin title of the work has Roman political and philosophical origins, evocative of the classical aspirations of the Federal US state. The word respublica means ‘commonwealth’, which Thomas’ translates as ‘of the people’. From the inception of this piece Thomas’ intention has been that her herstory paintings be accessible within a public art collection, hanging on the same walls as those of her male counterparts that felt a similar need to capture the landscapes of their own times. Her works like theirs ought to be understood as a civic asset. If this seems egotistical it is meant to be. In both the content and the concept of this work Thomas is challenging what she sees as the historic male artist superego face to face, on its own terms, as she says: ‘I have an ego, I have a gob’.

For Thomas, landscape painting is political with a small ‘p’, representing the ownership and economy of the land, literally the visual language of power. Pointing to how landscape painting has been used politically, symbolically demonstrating the ideology of nationalistic protectionism, Thomas vividly recalls Hudson River School landscapes being incorporated into the decorative scheme of George W. Bush’s Oval Office during the period of the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Paintings such as Rutland Falls, Vermont by Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) caught her eye whilst watching presidential addresses at the time which angered her in that these oases were now taking on 20th century associations of violence and war.

The history of landscape as a genre began in the sixteenth century with the topographical representations of the estates of local gentry and aristocratic patrons. To record and assert ownership through a visual image, to visually commodify what might, in an alternative worldview, be accessible to all. The English radical tradition is another key reference for Thomas with E P Thompson’s 1963 classic Making of the English Working Class the source for the title of this exhibition, taken from W Cobbett’s 1821 Rural Rides. Through Gina Thomas is asking a myriad of political questions: ‘who has control of the land? As a woman do I have permission to be here? And as a working-class artist what is my place in all of this?’

Taken as whole with the other works presented in this exhibition, Gina can be understood as central to Thomas’ radical intervention in the Fine Art canon, and her own radical acts in imaginary landscapes. In a strong thread that weaves throughout her practice, Thomas revels in the unsettling aspects of English Folk traditions: tits and cocks, dark fairy-tale forests, mummers’ plays, and the sinister looking Crow Men from her family village, Moulton. Gina confronts and conquers the phallic Beeston Castle crag throbbing in the distance. Could this be a case of Freudian Penis Envy? Not likely, that theory was discredited back in the 1920s, most notably by fellow psychoanalyst Karen Horney also credited with founding Feminist Psychology.

Gina is a hybrid painting, currently residing in Glasgow where Thomas is based, it features an American girl on an American Bike in a heightened visual representation of an English landscape. It should be read as an allegorical landscape into which Thomas poured big philosophical questions about sex, gender, class, war, and money at a very specific point in time. But like all allegories it has relevance and resonances beyond the specific moment gesturing towards universal truths.

Copyright Gráinne Rice 2021